Blog

Researchers develop underwater WiFi

The technology could enable divers to send information to the surface reliably and quickly. It’s quite cheap, too.

Quite cheap

The internet has become an indispensable tool, becoming essentially a human right. But while the internet has penetrated to some of the farthest corners of the world, there’s still one place it hasn’t yet reached: under water.

If you’re a diver or a marine researcher or explorer and want to send information from beneath the waves to the surface, you have three options: radio, acoustic and visible light signals. However, all these options come with significant drawbacks. For radio, data can only be carried over short distances, for acoustic the transmission speed is very slow, and for visible light, you need a clear path between the transmitter and receiver. If you wanted to have the best of all worlds, there was no possible option — until now.

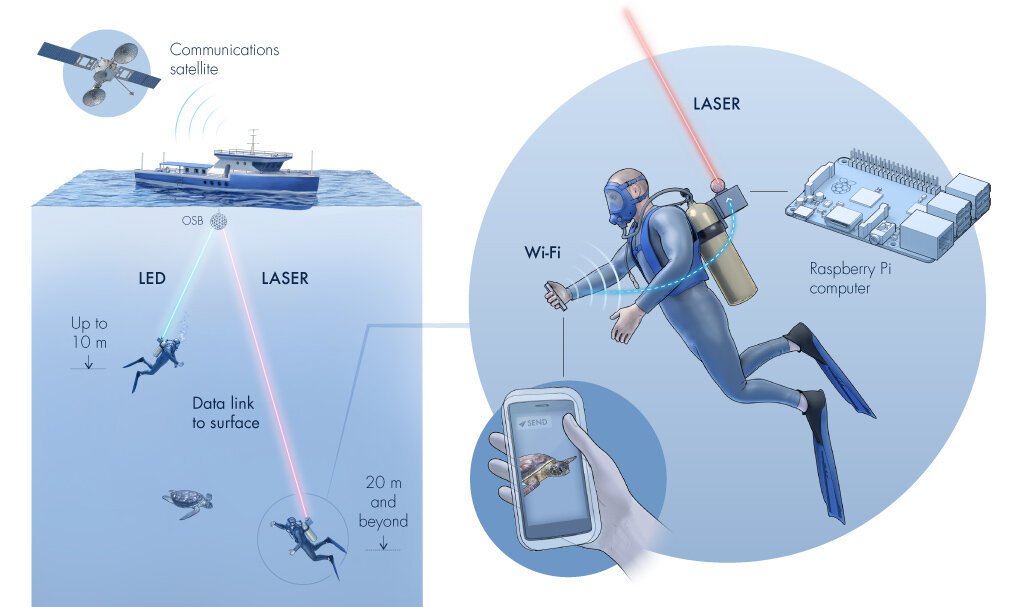

A team of researchers has developed a system for transmitting wifi under water, using lasers and LEDs.

“People from both academia and industry want to monitor and explore underwater environments in detail,” explains the first author, Basem Shihada.

The system, called Aqua-Fi, does not require any additional underwater infrastructure as it can operate using self-contained batteries. It also uses standard communication protocols, which means that it can communicate with other systems with relative ease.

Aqua-Fi uses radio waves to send data from a diver’s smartphone to a “gateway” device — the Raspberry Pi, the classic single-board computer used in engineering projects all around the world. The device then sends the data via a light beam to a computer at the surface

The researchers tested the system by simultaneously uploading and downloading multimedia from computers a few meters apart. The maximum speed they achieved is 2.11 megabytes per second, with an average delay of only 1 millisecond for a round trip.

To make matters even better, the whole system is cheap and relatively easy to set up.

“We have created a relatively cheap and flexible way to connect underwater environments to the global internet,” says Shihada. “We hope that one day, Aqua-Fi will be as widely used underwater as WiFi is above water.”

“This is the first time anyone has used the internet underwater completely wirelessly,” says Shihada.

However, this is more a proof of concept than anything else. The system used basic electronic components, and researchers want to improve its quality using faster components. They also need to ensure that the light beam remains perfectly aligned with the receiver in moving waters.

So it will still be a while before Aqua-Fi becomes publicly available, but it’s getting there, the team concludes.